For the last 30 days I replaced all the red meat, white meat and fish in my diet with edible insects. I took before and after blood tests, physique pictures and tracked my recovery from exercise with my Whoop strap.

Original Diet

My original diet was aimed at getting the correct amount of protein, carbohydrate and fat each day. It’s generally a “clean” diet, with protein coming from grass fed beef, chicken breast, salmon and mackerel. My non-meat sources of protein include Greek yoghurt, eggs and Pea & Rice protein powder.

Since I control and track my protein intake, I first needed to establish how much I was getting from meat & fish. The plan was to then make a direct swap to edible insects. Across 30 days I ate the following:

- 1.93kg of red meat

- 1.20kg of white meat

- 1.71kg of oily fish

The total protein content across all three sources was 1036 grams, equivalent to 35 grams of protein per day from meat & fish.

New Diet

I’ll be honest, I didn’t look at too many options before settling on edible crickets. There are several UK companies and I chose Horizon Insects. In their dried form crickets are close to 70% protein, roughly three times that of chicken or beef, meaning to replace all my meat I’d need to eat 50 grams a day. That worked out nicely at a 30 day requirement of 1.5kg, which I purchased in the form of three 500g bags. This set me back £78, though the website has since doubled their prices due to higher operating costs.

My Eating Experience

Things didn’t get off to the best start. My first meal involved frying them in oil, then adding them to mushrooms & rice. As they were dry it left them incredibly chewy, requiring around 20 minutes to work my way through the whole bowl. The taste was somewhat masked by hot sauce but the texture was quite off-putting.

Beyond day one it was much improved. I added tomato passata to give them back some moisture before frying them again and adding them to a wrap. I also added in other sources of “crunch” like bell peppers to mask the texture. Rehydrating with passata was something I tried several more times, including simple dishes like crickets and pasta.

I tried three recipes which used the ground version, first blending them into a powder (which retailers also sell directly). There’s my no bake flapjack recipe which was a straight swap from whey protein to cricket flour, as well as cricket flour banana pancakes and my personal favourite, the cricket burger.

The taste is sometimes described as “nutty” but I prefer the term “earthy” – not dissimilar to my vegan protein powders. They are certainly not pleasant but neither do I consider them to be disgusting. You are unlikely to create a recipe where they taste delicious, because by definition any recipe would taste even better if it didn’t contain insects!

The Results

I had plenty of different ways to assess my change in diet, each of which I’ve rated out of 10.

My Gym Experience

According to my Tanita scales, I started this experiment weighing 69.9kg with 16% bodyfat. Thirty days later I was 70.1kg and 16.1% bodyfat. Since the calories and macronutrients were a straight swap this wasn’t surprising.

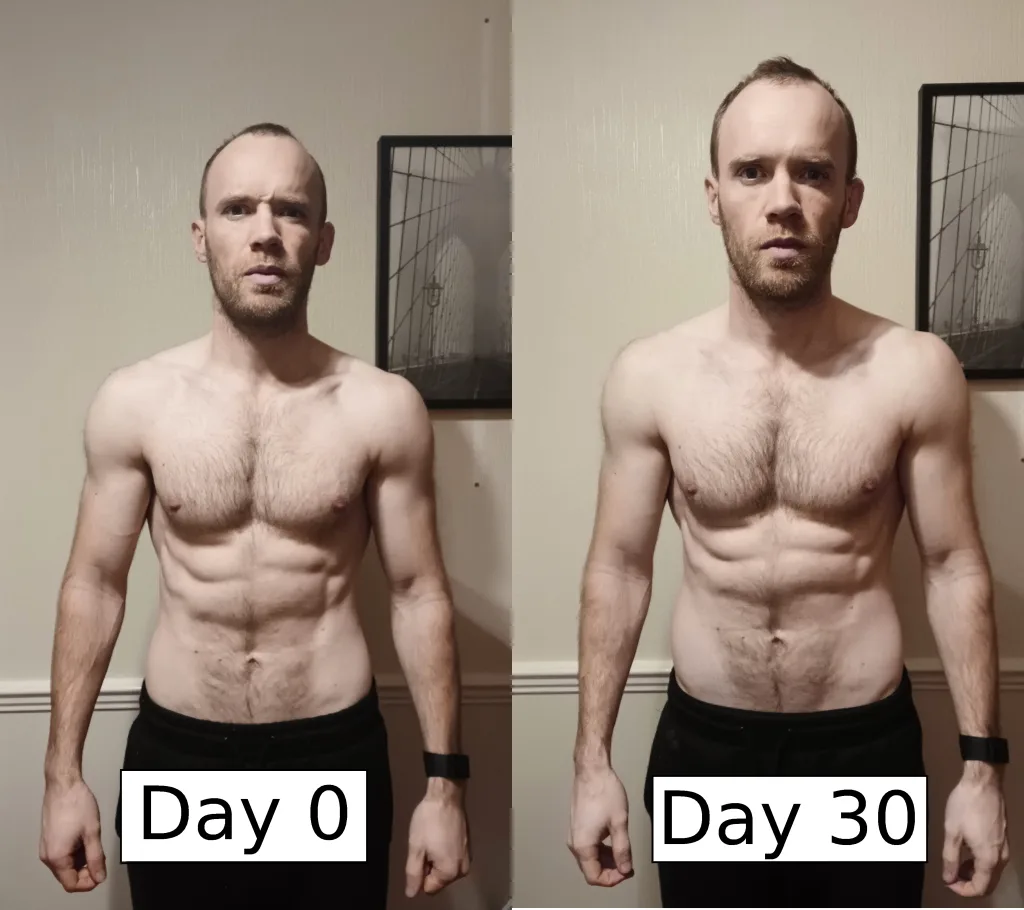

I also took topless physique pictures at the beginning and end of the experiment, here’s how they compare:

To be honest I’m not sure how much change you’d see in 30 days given my dietary protein intake was maintained. That being said, I did notice changes in the gym.

I’ve exercised for enough years that I feel very in tune with my body and I’m able to detect small changes. Within three or four days of eating crickets I felt that I wasn’t recovering as well between workouts, gaining more cumulative fatigue than usual. This immediately reminded me of my 8 week trial on the longevity diet, where I cut my protein by around 30%. That caused me to pick up several niggling injuries that took much longer to go away, and it was the same case here. I strained my pec during bench press and also the top of my hamstring during squats, and those lingered for 1-2 weeks before improving.

Gym Rating: 3/10 (clearly worse)

Cricket Protein Bioavailability

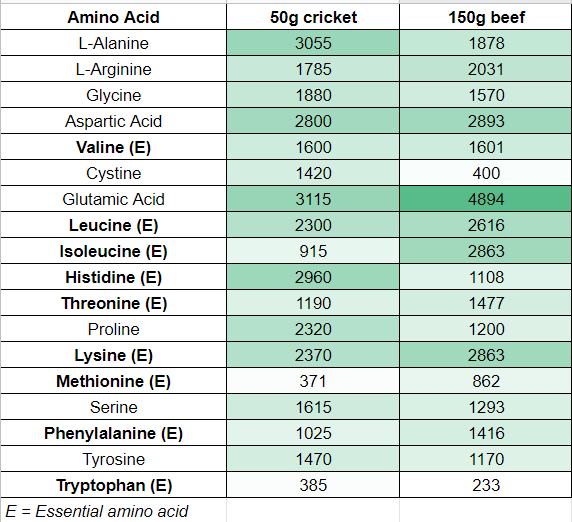

The only reason I can think of is that either the amino acid profile is vastly different for crickets, or there’s some issues with bioavailability. It’s known that some plant-based proteins aren’t utilised by the body as well as meat and it may be the case for crickets. Below is the amino acid profile for a portion of crickets and beef that each deliver 35 grams of protein.

Crickets are only significantly lower in Glutamic Acid, Isoleucine and Methionine. Isoleucine is one of three branch chain amino acids (BCAAs) but another BCAA, leucine, is more important for muscle recovery. Methionine’s main role is in detoxification and Glutamic Acid has more of a role in brain function. It may well be that the values quoted here are not reflective of exactly the foods I ate.

As for bioavailability, the research was mixed. It’s tempting to only cite articles that align with my belief, such as this report stating we overestimate the protein content of insects. Arguments against insect consumption also mention chitin, an indigestible fibre which can hinder protein availability. The cooking methods can also make a difference, with boiling found to reduce the protein content of crickets by around 10% (note that mine were either fried or oven roasted). A study assessing something called “protein disappearance” found insects to be inferior to plant-based proteins, with the exception of raw soybeans. That study showed oven cooked crickets were less digestible than plant proteins and casein (milk protein).

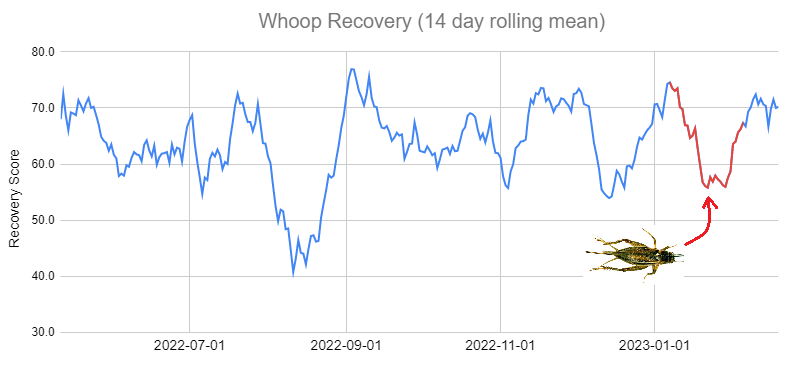

My Whoop Data

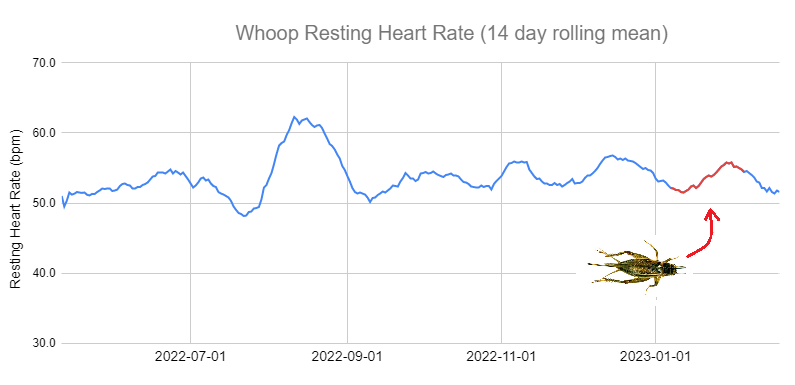

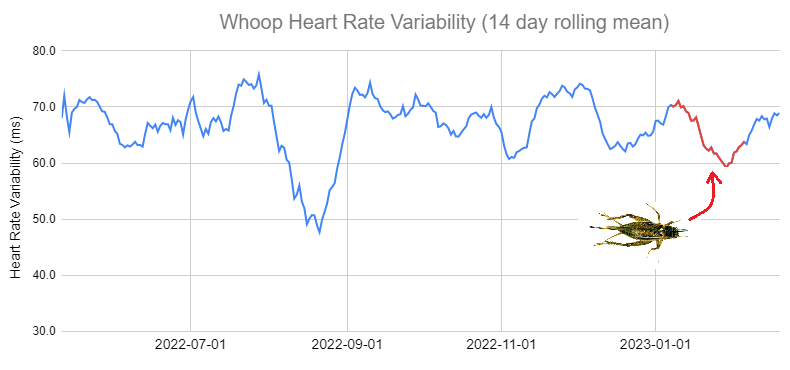

I’ve been wearing a Whoop Strap for the last 9 months and it’s useful as an extra source of data. I had a look at my resting heart rate, heart rate variability (HRV) and Whoop’s own recovery score, a measure of how ready I am for activity that day. Note that with HRV a higher score is generally better.

At the beginning of August 2022 I had a tooth infection and a horrible 10-14 days on antibiotics. This serves as a useful comparison in all my graphs. While my heart rate did go up on the cricket diet, it had 2-3 similar fluctuations in the previous months.

The heart rate variability (HRV) data aligns with what I felt at the time – that I wasn’t recovering well. I even had to reduce my training load on some days for fear of injury. The graph only comes back again in the final week as that coincided with tapering for a competition. You can see that with the exception of my tooth infection in August 2022, my average HRV hit its lowest all time level after 3 weeks of eating crickets.

Whoop’s recovery score factors in other variables like sleep, but it does give a lot of weight to HRV. It also shows a steep drop off as the cricket diet is introduced and an upturn as I taper for competition. Overall the data supports the sense that my body was not able to maintain the same training intensity and volume when partially fuelled by crickets.

Whoop Rating: 4.5/10 (generally negative)

My Blood Test Results

Protein is only one nutrient, and it may be that other vitamins and minerals are higher or lower after my diet swap.

Cholesterol

I’ve had five cholesterol tests in the last three years, and the results following the cricket diet were:

- Lowest Total Cholesterol (4.3mmol/L) vs 4.98mmol/L average

- Lowest LDL “bad” Cholesterol (2.5mmol/L) vs 2.83mmol/L average

- Lowest HDL “good” Cholesterol (1.53mmol/L) vs 1.71mmol/L average

- No real change in Triglycerides

In percentage terms, that’s a drop of 14% in total cholesterol, 12% drop in LDL and 11% drop in HDL.

Testosterone

I’ve also had five testosterone tests in the last three years, with the following results:

- Second lowest Testosterone (24.5nmol/L) vs 26.21nmol/L average

- Lowest free or unbound testosterone (0.343nmol/L) vs 0.442nmol/L average

Iron Profile

I’ve had four iron profiles in the last six years, with the following results:

- Lowest Ferritin (104ug/L) vs 126.4ug/L average

- Highest Iron (29.9umol/L) vs 23.9umol/L average

Other Biomarkers

- Omega 3 Index dropped from 12.19% to 9.85% (June 2022 vs Feb 2023)

- Omega 6:3 ratio rose from 3.7 to 6.1 (June 2022 vs Feb 2023)

- Folate rose from 13.1nmol/L to 15.9nmol/L (Dec 2022 vs Feb 2023)

A quick search confirms that crickets are indeed high in iron and folate. While meat is a good source of iron, it is typically low in folate (unless opting for beef liver). The omega 3 in my crickets across the 30 days totals 42 grams, while the amount I missed out on from eating mackerel is 94 grams. Note that beef and chicken are both poor sources of omega 3, and at 9.85% my omega 3 index is still considered optimal.

Current advice states that animal fats can raise cholesterol, and seeing my cholesterol drop by 0.5mmol/L since October potentially backs that up. Red meat and oily fish are both said to aid testosterone levels, and cutting out both saw my levels of free testosterone drop by 22%. The final consideration is that dietary changes can take 90-120 days to be fully reflected in biomarkers like Omega’s and cholesterol. That means my values may be more of an indication of the direction they’re going rather than their new levels.

Biomarker Rating: 6/10 (mixed)

My Climate Impact

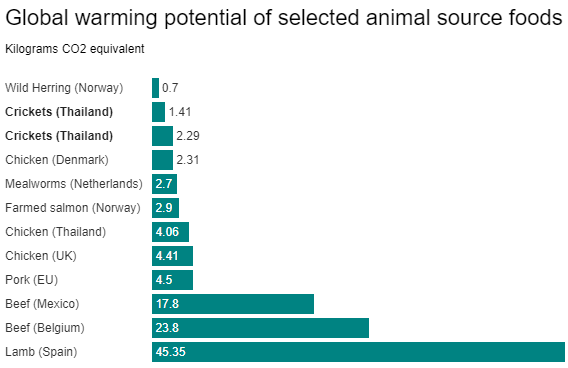

The whole reason we’re being encouraged to eat insects is for the effect on climate change. Firstly let’s talk CO2, carbon dioxide, which forms your carbon footprint. The units of measurement are the kilograms of CO2 emissions to produce one kilo of the product.

The first number I found for beef was 60kg of CO2 per 1kg finished product, but it varies a lot by country. Revising my search for UK beef brought that down to 17.1kgCO2, with a global average of 46kgCO2. My other protein sources are much more reasonable, UK chicken is 4.4kgCO2 and fish is 2.6kgCO2.

So how about crickets? The data that is quoted a lot, including in the above chart, comes from Thailand, where it’s around 2kgCO2 per 1kg product, so less than half of chicken. Remembering that crickets contain three times as much protein as meat per kg means it’s about a third that number when considering a per portion value.

However, my crickets were grown in the UK. Since crickets are raised in temperatures around 25°C the process requires more heating, as the UK climate is 10-20°C colder than Thailand. I found a paper that tried to calculate the UK carbon footprint of rearing edible crickets. They obtained a per kg value of 21.1kgCO2. Dividing by three to account for the protein content still gives a value of 7kgCO2, 50% higher than UK chicken per serving.

Crickets vs Meat: The Numbers

Using these values I can then calculate the change in CO2 from eating crickets:

- 1.2kg Chicken at 4.41kgCO2 = 5.29kg CO2/month

- 1.93kg Beef at 17.12kgC02 = 33.04kg CO2/month

- 1.71kg Oily Fish at 2.6kgCO2 = 4.45kg CO2/month

- Original Diet: 42.78kg CO2/month

- 1.5kg Crickets at 21.1kgCO2 = 31.65kg CO2/month

- New Diet: 31.65kg CO2/month

The difference is around 11kg CO2. That’s equivalent to one of the following:

- Driving 55km in a petrol car

- Running the washing machine 20 times at 30°C

- 4 Dozen eggs

- A single passenger cruising on an airplane for 7.5 minutes

While the move to eating crickets might not have an enormous impact on CO2, there are other environmental issues with eating meat. Cattle require far more water, produce more methane and their need for farmland is driving deforestation. Here’s an article by the World Wildlife Fund about the environmental impacts of meat and dairy.

Climate Rating: 8/10 (CO2 is overhyped, other factors underhyped)

Conclusions

Overall it was a beneficial experience and encouraged me to do a lot more background reading on climate change. Here’s a few things I’ve learned:

- I wasn’t previously aware how much beef differed from chicken and fish in its climate impact. Over 75% of the CO2 from my meat & fish comes from the 1.9kg of beef I eat each month. Instead of swapping everything to crickets, I can have the same impact swapping 1kg of beef for chicken.

- If I want to cut my CO2 emissions, I’m better off doing it elsewhere. By opting to travel by train for an upcoming wedding overseas, I’m able to save around 260kgCO2. That’s the same carbon footprint as 15kg of beef – about 8 months worth of my current diet.

- It’s quite easy to spend 30 seconds on Google and find an answer that aligns with your beliefs. A better approach is to dig deeper, maybe even venturing onto page 2 (!), to get a broader picture. It also helps to find articles backed up by research, otherwise you don’t know where the numbers are coming from.

- Protein content isn’t everything. There’s plenty of vitamins and minerals that food delivers and it shouldn’t be overlooked. You can also find that digestion/bioavailability varies enough that foods with a high protein content are often not what they seem.

While I didn’t need to overhaul my diet quite so dramatically, doing so helped reach conclusions sooner. I wonder how I’d feel in the gym if I only ate crickets once a week, or what my blood test results would show? A lot of what we measure is subject to “noise”, meaning the numbers move up and down based on all the other factors in your life. If you want to see something significant that means making a bigger initial change. There are of course potential side effects and I did a great deal of reading prior to starting this diet. Swapping all my red meat, white meat and fish for edible insects for 30 days was certainly a big change, and it’s something I won’t be repeating any time soon 🙂