Your Resting Heart Rate, sometimes abbreviated RHR, is the number of times your heart needs to beat in 60 seconds at rest. A lower resting heart rate is associated with better cardiovascular health, but a number of conditions can affect how fast your heart beats at rest.

How to Measure Resting Heart Rate

While there are now wearables that constantly track resting heart rate, the most reliable method involves counting it yourself. It’s recommended that you measure resting heart rate first thing upon waking, even before you get out of bed. Here’s how to do it:

- Upon waking, remain lying down or prop yourself up slightly with a pillow

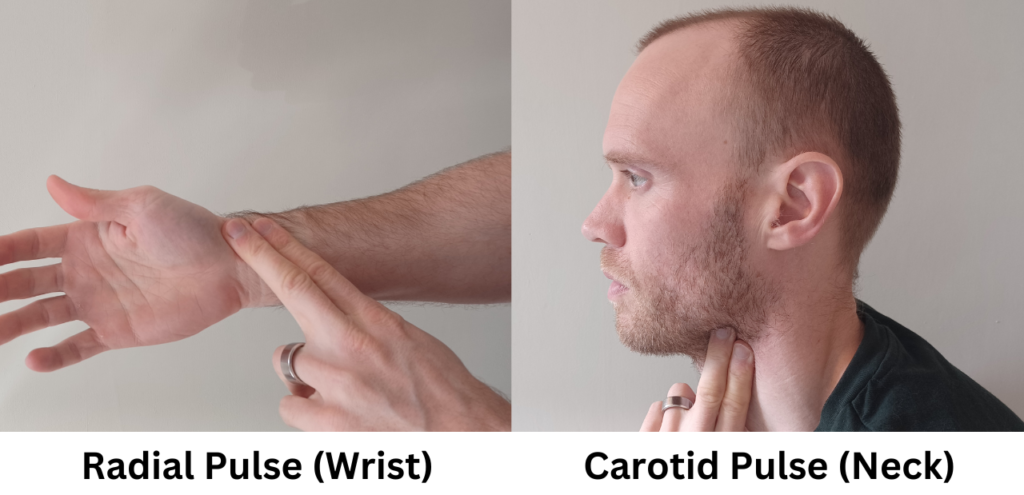

- Once you are settled, you will need a timer and to locate your pulse. Common places include the inside of your wrist or neck.

- Start the timer and immediately begin counting.

- Once a full minute (60 seconds) has elapsed, stop counting.

- Record your resting heart rate, the units of which are beats per minute (BPM).

- Consider re-measuring in a few days time.

It’s often suggested that you count for less than 60 seconds and multiply the result. For example, counting for 15 seconds and multiplying the number by 4. However, the shorter you count for, the less accurate your result is likely to be. If you only count for 15 seconds, a true resting heart rate of 54 will only be measured as 52 (13 beats in 15 seconds) or 56 (14 beats in 15 seconds). It all depends how precise you need the number to be.

What do my results mean

For people without any health conditions, your resting heart rate can reflect your overall fitness and heart health. There are, however, several factors that can influence the result.

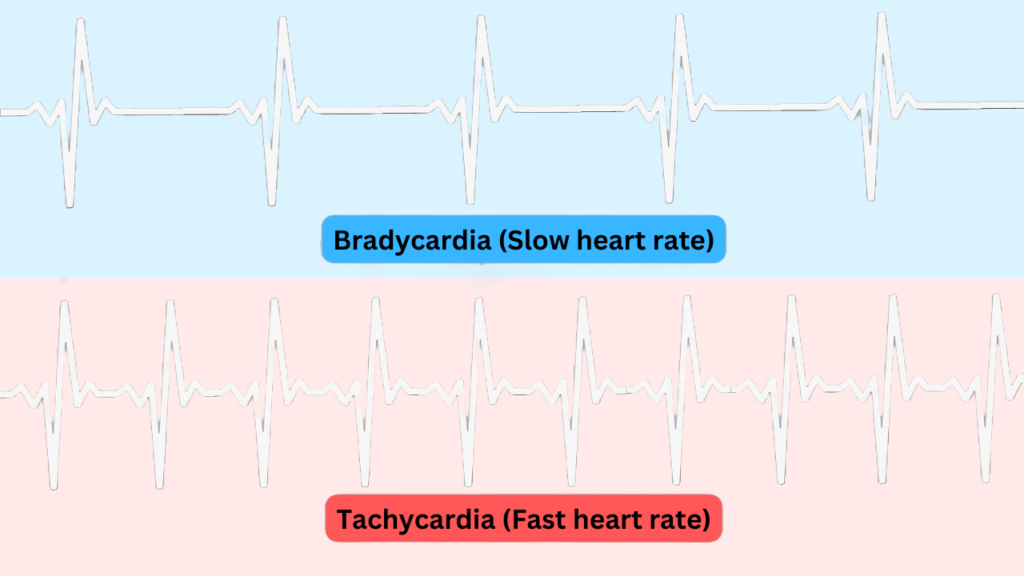

Bradycardia (Slow heart rate)

Bradycardia is the general term for a slow heart rate and captures a multitude of conditions. Accompanying symptoms might include fatigue, dizziness or lightheadedness, confusion, shortness of breath and fainting. This is due to your body failing to supply adequate blood flow to the brain.

While technically a heart rate below 60 beats per minute qualifies as bradycardia, if you are physically fit you will likely fall below this number. Medical reasons for a slow heart rate include low thyroid hormone, infection of the heart tissue, damage to the heart from surgery or heart disease and some inflammatory diseases like lupus. If you are concerned about your low resting heart rate it is best to speak with a medical professional.

Tachycardia (Fast heart rate)

At the opposite end of the scale is a faster than normal heart rate, known as tachycardia. Your heart will work harder in response to exercise, but if it’s above 100 beats per minute at rest this would qualify as tachycardia.

The most common reason is a heart arrhythmia, which simply means an abnormal heart rhythm. As with bradycardia, it may cause fatigue, dizziness or lightheadedness and shortness of breath. It may also be accompanied by chest pain and you may be more aware of the sensation of your heart beating. If you are concerned about your high resting heart rate it is best to speak with a medical professional.

Cardiovascular fitness

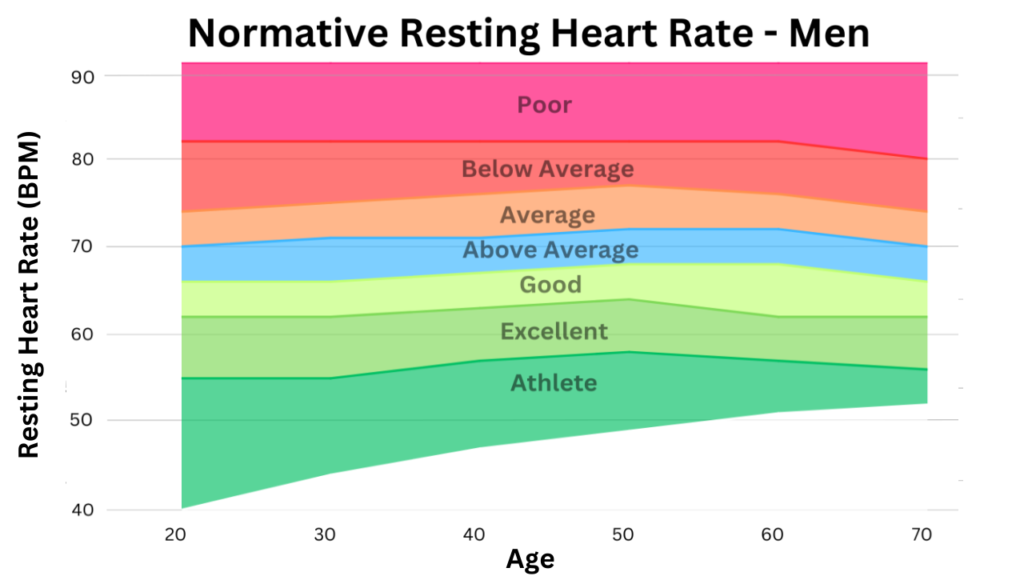

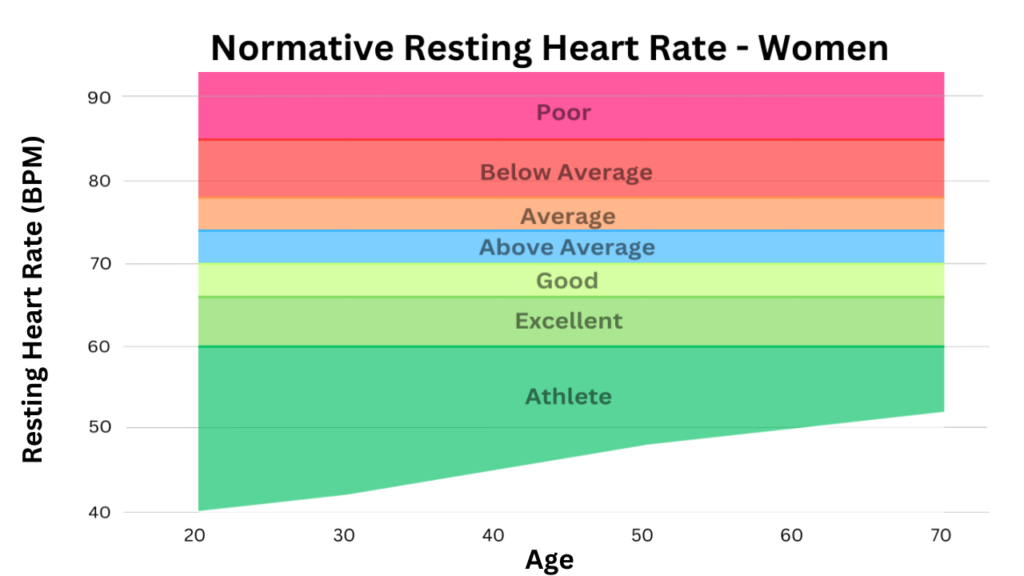

Moderate or high intensity exercise challenges your heart muscles and as a result they go stronger. This means they can pump more blood per heartbeat, and so at rest your heart doesn’t have to beat as often. Conversely, sedentary individuals who are not working their heart muscle may find it gets weaker and requires more beats per minute at rest.

Over time, your heart muscles will become less efficient, and so resting heart rate generally increases with age. However, this is a subtle effect, as you’ll see in the following charts. Additionally, women tend to have smaller hearts than men, so they have different normative values.

These values are general guidelines, and as you can see anything below 66 beats per minute is considered “good” for a man. A resting heart rate above 75 bpm would be labelled “below average” or “poor”.

For women the values are slightly higher, so “good” would be below 70 bpm and “below average” or “poor” above 78 bpm.

Tracking Heart Rate Over Time

As you can see by the graphs above, for a given fitness level you are unlikely to see dramatic changes as you age. However, you are far more likely to see rapid changes as a result of a change to your fitness level. For a sedentary individual undertaking a new exercise program, you may see an initial reduction in resting heart rate by up to 1 beat per minute each week.

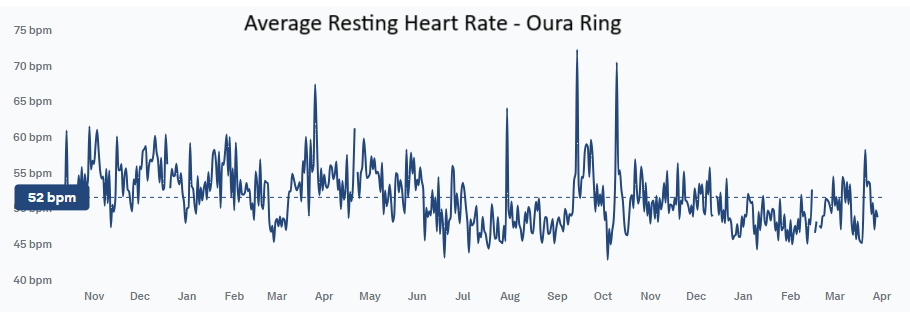

Here I’ve added my own average resting heart rate over time, as detected by my wearable Oura ring. The spikes are periods of illness and the average is closer to 56 bpm in the first half of the graph and 50 bpm in the second half.

It’s also important to note how spiky the graph is over the short term, indicating that my heart rate on consecutive weeks may differ by as much as 7 or 8 beats per minute depending on the day I measure it. This is likely an after effect of hard training, as the body will be recovering the next day, leading to a higher resting heart rate. With that in mind, you may wish to measure your heart rate several mornings in a given week to establish a baseline. Beyond that, it’s worth rechecking every 3 to 6 months, particularly if you are following an exercise plan.